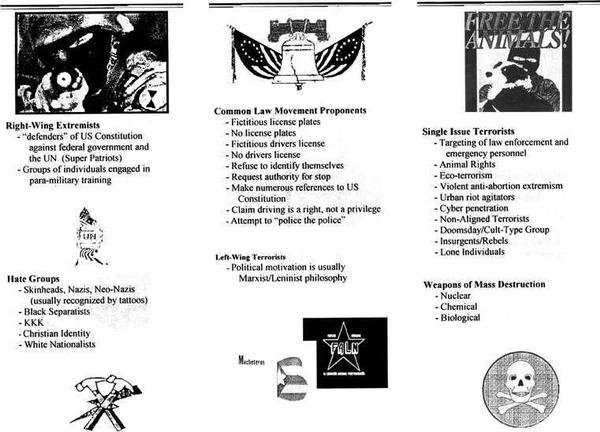

aristotelian theory is especially important when it comes to issues like discerning the "original intent" of the constitution--that is, whether such a thing is possible at all, or whether it is to be left to the whims of the democratic process, where the "majority" has the potential of voting pretty much *all* our rights away. in the sense that postmodern literary criticism understands meaning to come not from the "original intent" of the author but rather the dynamic interplay between the reader's class/race/ethnicity/whatever and the author's vague traces of presence, it seems to only further the predominantly leftist/liberal agenda of the state-sponsored academic elite with their notion of an infinitely malleable or "living" constitution that is to be read one way or another depending on the dominant social paradigm at the time--which gives one the impression that our "inalienable" rights may not be part of our original nature after all, but are rather something ascribed to us by the dictates of our platonic guardians, i.e. the supreme court judges who have not only taken it upon themselves to "translate" the constitution for us (how nice of them!) but also to let us know when it is *proper* to speak or own property or bear arms within certain limits (which they prescribe, of course).

anyway, enjoy!

THE FOUNTAINHEAD: EXCERPT

INTERVIEW WITH MIKE WALLACE: PART 1

INTERVIEW WITH DONAHUE: PART 1

The Romantic Manifesto

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature is a non-fiction work by Ayn Rand, a collection of essays regarding the nature of art. It was first published in 1969, with a second, revised edition published in 1975. Most of the essays originally appeared in The Objectivist, except for the "Introduction to Ninety-Three", which was an introduction for an edition of the Victor Hugo novel. The revised edition added the essay "Art and Cognition".

At the base of her argument, Rand asserts that one cannot create art without infusing a given work with one's own value judgments and personal philosophy. Even if the artist attempts to withhold moral overtones, the work becomes tinged with a deterministic or naturalistic message. The next logical step of Rand's argument is that the audience of any particular work cannot help but come away with some sense of a philosophical message, colored by his or her own personal values, ingrained into their psyche by whatever degree of emotional impact the work holds for them.

Rand goes on to divide artistic endeavors into "valid" and "invalid" forms. (Photography, for example, is invalid to her (qua art form) because a camera merely records the world exactly as it is and has very limited, if any, capacity to carry a moral message beyond the photographer's choice of subject matter.) Art, to her, should always strive to elevate and idealize the human spirit. She specifically attacks Naturalism and Modernism in art, while upholding Romanticism (in the artistic sense, not in terms of general philosophy).

Rand states unequivocally that the primary purpose of her art is to glorify the triumphs of free will through the heroic actions of heroic characters.

The book ends with a short story entitled "The Simplest Thing in the World".

What is Living in the Philosophy of Ayn Rand

by Lester Hunt

If I had to say which part of Ayn Rand's philosophical work is most unjustly neglected, and most likely to yield pleasant surprises when it is eventually discovered and exploited, it would certainly be her writings on aesthetics. The clarity and systematic rigor of her core writings on this subject - namely, the first three essays in The Romantic Manifesto - suggest very powerfully that she thought her position on these issues through as thoroughly and carefully as she did her views on any other subject. It has always seemed a shame to me that these writings are so seldom discussed in the secondary literature and that they have influenced, in comparison with the rest of her output, a relatively small group of people. The single virtue of these writings that I find most valuable today is also one that strikes me as the cardinal virtue of all of her work: this is a trait that I like to think of as her "radicalism," a term that I mean in the very literal sense of a tendency to approach an issue in terms of its root (radix) in the issues that underly it.

Perhaps the best way to indicate what I have in mind, both what this trait is and why it is a virtue, is to say a word or two about how her work in this area is related to a recent debate in literary theory. I have in mind the recent controversy between Judge Richard Posner and Professor Martha Nussbaum on the relation between morality and literature.(1) In it, Posner defends that view that aesthetic value, the value that is distinctive of a work of art, is not only distinct but separable from moral value, and that, where imaginative literature is concerned, moral properties of any sort are "almost sheer distraction."(2) Nussbaum insists, for her part, that it is a very important fact about literature that it provides us with a particular sort of moral enlightenment and character-improvement: the sort of "uplift" one gets from Charles Dickens, in which we learn to be compassionate toward the little fellow.

I would expect that many people find the general tendency of this discussion extremely unsatisfying. On the one hand, the deep sterility of Posner's conception of literature is difficult to escape. On the other, he does score some palpable hits against Nussbaum's view. Most devastating, perhaps, is his pointing out that the books that she picks out as clearly embodying her theory-such works as Wright's Native Son and Forster's Maurice - are not the clearest examples of artistic greatness. To my way of thinking, perhaps the most telling case in point is one that Posner does not take advantage of, and that is Dickens' Hard Times. I find it shrilly and tediously didactic, and yet it seems to be precisely the sort of work she is must recommend to us. In fact, her presentation of her theory in Poetic Justice virtually takes the form of a commentary on Dickens' book.

A more deeply frustrating aspect of the debate is one about which Rand would very obviously have something to say. This is the fact that, in it, the nature of literature, and of art in general, are left unexamined. Posner is claiming that art, whatever it might be, does not need morality, and Nussbaum is claiming that art, whatever it is, is even better if one adds morality to it. The position she takes is thus actually wide open to a certain Posnerian counter-charge. Most of the argument of her Poetic Justice consist of attempts to show how literature can have good moral effects on us. Such a case, even if it is made out, is perfectly consistent with the view that literature is an intrinsically amoral object which becomes good for us when it is turned toward moral purposes. Judge Posner can simply point out - as, in effect, he does - that these arguments do not show that the addition of morality to literature makes it better as literature. On the other hand, his own positive argument consists mainly in examples which tend to indicate that morally good works can be inferior literature while works expressing unsound moral and political theories can be great. These arguments are almost entirely intuitionist, in that they merely appeal to presumptive judgements of literary merit that we already have, and stop there. Neither side of this debate, however, presents an account of what art and literature are. In effect, the debate is carried on as if art were, as Rand would put it, an "irreducible primary," something that can explain other things but cannot itself be explained.

On this point Rand departs radically from the approaches of both Posner and Nussbaum. Just as, in her ethics, she begins by asking, not which values are right but why there are any values at all, so in her aesthetics she does not begin by asking what makes art better or not so good, but why there is any art at all.With her distinctive drive toward the most radical, the most fundamental concepts, she poses an answer based on the nature of consciousness and the requirements of human survival. In order to plan their lives and give them unity, she maintains, human beings need to have a view of the nature of the world in which they live and of the value of broad categories of concerns that depend on human action.They need to have serviceable answers to questions like these:

Can man find happiness on earth, or is he doomed to frustration and despair? Does man have the power of choice, the power to choose his goals and to achieve them, the power to direct the course of his life

- or is he the helpless plaything of forces beyond his control, which determine his fate? Is man, by nature, to be valued as good or despised as evil? These are metaphysical questions, but the answers to them determine the kind of ethics men will accept and practice; the answers are the link between metaphysics and ethics.(3)

Rand calls the abstractions that answer such questions "metaphysical value judgments." They are so broad, and the entities subsumed under them are so various, that no human mind could adequately apply the principles involved directly to reality. An intermediary is needed, something that can bridge the crevasse that yawns between the abstract and the concrete. This intermediary, according to Rand, is art, though art conceived in a sense much wider than high art as we usually conceive of it. It is wide enough to include myth, legend, religious icons, and popular television shows. Art is a selective recreation of reality projecting fundamental abstractions into the only medium in which they can be readily grasped: that of perceptual concretes. Without such projections, the human mind would not be able to fully carry out its function as part of a living organism.Thus conceived, the role that judgements of value play in literature, and in art in general, is much more profound than that put forward by Nussbaum in her exchanges with Posner. If Rand is right, then art will be particularly apt to be turned to the ends to which Nussbaum suggests it be turned, those of instructing us in previously unknown moral truths and molding our character. But the judgements which are essential to art, and make it a necessity of life itself, concern matters that are anterior to the comparatively petty issues with which Nussbaum is concerned. The function of art is not to express moral, political, or economic theories, but to embody ideas about the nature and possibility of human life, and its value.

If we assume that Rand is right about this, we can readily explain why works that vividly exemplify Nussbaum's theory can be artistically mediocre. She chooses the wrong sorts of issues for art to be about. Though art can deal with such issues and should, this is not the sort of function that makes it art, nor is it the sort of function that gives art value that it has by its very nature. More particularly, the sort of moral enlightenment Nussbaum recommends can easily degenerate into didacticism, and the egalitarian sympathy

-based ethic she believes in can produce sentimentality, and often does.

From Rand's point of view, Posner would be seen as making the very same mistake, that of misidentifying the way in which literature would be linked with morality if there were such a connection, though he takes the error and draws the opposite conclusion from it: that no connection exists. The Posner-Nussbaum controversy illustrates several of the sorts of damage that follow from a failure to be sufficiently radical. These would include the trivialization of deep issues, the creation of false dichotomies in which entire alternative theories become invisible, and the creation of unsatisfying discussions, in which all participants seem to be both right and wrong - right in what they deny, but wrong in what they assert.

1. 1. Posner's original contribution, at least in print, was "Against Ethical Criticism," Philosophy and Literature, (April, 1997), vol. 21 no. 1, pp. 1-27. This was a criticism of Nussbaum's Poetic Justice: The Literary Imagination and Public Life (Boston: Beacon Press). This exchange of views recently took the form of a lively symposium, which featured not only Posner and Nussbaum but an extremely helpful presentation by Wayne Booth, at a May 9th, 1998 session of the Central Division Meetings of the American Philosophical Association.

2. 2. Ibid., p. 24.

3. The Romantic Manifesto (New York: Signet, 1971), p. 19.

Foundations Study Guide: Literary Theory

by Stephen Cox, PhD.

Stephen Cox is professor of literature and director of the humanities program at the University of California, San Diego

Literary theory attempts to establish principles for interpreting and evaluating literary texts. Two of the most important issues in literary theory are authorial intention and interpretive objectivity. Is the author's intention responsible for the meanings of a text? Can readers arrive at an objective understanding of those meanings? Currently fashionable theory answers no to both questions. It suggests that meanings are created and recreated by influences beyond the control of either writers or readers. This view is diametrically opposed to the classical tradition in literary theory.

Aristotelian Theory

Aristotle originated the kind of literary theory that emphasizes the objective features of texts and the authorial intentions that those features reveal. He sought to explain and evaluate literature as a product of human design. His Poetics analyzes the objective features of Greek epics and dramas as means that are more or less appropriate to the full realization of various literary intentions.

In Aristotelian analysis, text-making intentions are understood as distinct from social influences and psychological motives. Aristotle appreciated the fact that Greek playwrights derived their themes and stories from the commonly held attitudes and commonly recounted myths of Greek society. He also knew that playwrights might be motivated largely by the desire to win prizes and other forms of public recognition. A psychologist or sociologist might perform an interesting analysis of these background influences on a play—without even beginning to explain and access the choices that its author made to produce the specific artistic effects that he intended. That, however, is the task to which Aristotle addresses himself as a literary theorist.

A classical example of Aristotle's analytical method is his treatment of the tragic protagonist. As Aristotle suggests, an author who intends to arouse the tragic emotions of "pity and fear" must choose his means of doing so, and the available means can be rationally estimated. The author can choose a central character who is perfectly bad, perfectly good, or somewhere in the middle. The downfall of a perfectly bad character would be comic, not tragic; the downfall of a perfectly good character would be merely hateful. The choice of an "intermediate" character is therefore the appropriate means of producing the tragic effect. The downfall of such a character can arouse pity for the defeat of good qualities and fear for the results of bad ones.

Aristotle's concern with the rational adaptation of literary means to literary ends includes concern with the unity of literary works. He assumes that an author's various purposes should be consistent with one another and that every element of a work—plot, character, style, and so forth— should contribute to those purposes, not frustrate or divert attention from them.

One interesting thing about Aristotle's literary theory is that it is not culture-bound. Although the Aristotelian standard of unity (for instance) is exemplified in certan works of the Greeks, it is not applicable merely to Greek or even Western Art. The Aztec lyric is governed by different intentions from those of Greek tragedy, but it can be rationally assessed in regard to its consistency and efficiency in fulfulling those intentions.

Aristotelianism after Aristotle

In the hands of later practitioners, especially those of the Renaissance, "Aristotelian" theory often degenerated into a system of rules that were far from universally applicable. But essentially Aristotelian assumptions were likely to come into play whenever critics of any school made a serious effort to assess works or authors according to their ability to accomplish their literary intentions.

For example, during the Enlightenment, the first great age of English criticism, leading critics informed themselves as best they could about the distinctive intentions of the authors they studied and analyzed the degree of skill that those authors showed in choosing literary means appropriate to their ends. Two of the most impressive works of that age, Alexander Pope's An Essay on Criticism and Samuel Johnson's Preface to Shakespeare, are attempts by cultivated readers to recover the principles by which great authors practiced their craft.

During the Romantic period of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, literary theory often based itself on psychological or social speculation rather than objective analysis of artistic strategies. Nevertheless, the best of this Romantic theory is significant for its emphasis on the individual mind as creator of meaning and organic unity in literary works. Shelley's A Defence of Poetry depicts poets not simply as creatures of social circumstances but as "the unacknowledged legislators of the World." Coleridge's Biographia Literaria argues that real poetry displays a unity of "the general, with the concrete; the idea, with the image," and that this unity is imposed by the individual creative imagination.

In the twentieth century, Ayn Rand produced a unique combination of Romantic and Aristotelian approaches to literary theory. The essays collected in her Romantic Manifesto advocate a literature produced by rational selection, in the Aristotelian manner, and marked by imaginative unification or "integration," in the Romanitc manner. Rand's definition of art as "a selective re-creation of reality according to an artist's metaphysical value-judgments" is widely applicable. It identifies the process of choice by which artists convert their contexts—"reality," as they understand it—into specific literary texts.

Current Controversies

It cannot be said that the late twentieth century is the golden age of either Romantic or Aristotelian theory. Currently fashionable theory is animated by the assumptions of Marx, Freud, and such contemporary continental thinkers as Michel Foucault. It is preoccupied with the ways in which political or psychosocial phenomena affect the processes of writing and reading. Its crucial assumption is that literature is "constructed" not by authors but by environmental influences, and that neither authors nor readers can "transcend" such influences.

One of the weaknesses of such theory is its inability to account for the ways in which very individual texts emerge from general contexts. Shakespeare's Macbeth is about (among other subjects) the political problems of a hierarchical society. The play's political context is a necessary condition for its existence—but not a sufficient condition. If context were sufficient to "construct" the salient features of the play, then the political environment of Elizabethan England would have produced thousands of Macbeths.

Readers as well as writers exist in political contexts, but if they could not transcend those contexts and arrive at a comprehension of works produced in environments very different from their own, then Macbeth would have run out of readers long ago. The same logic applies to theories of psychosocial construction. Many people have had miserable relationships with their fathers, but there is only one Brothers Karamazov, and the novel can be read and understood even by orphans.

The effects of current theories are not all bad. They have led critics who instinctively oppose them to refine their own ideas and account for what went wrong with those of other people. Some of the most valuable critiques of current theories, especially those descended from Marx and Freud, can be found in Frederick Crew's book Skeptical Engagements. Gerald Graff, in Literature Against Itself, provides a well-argued account of the mistaken assumptions that underlie postmodern theory. (Unfortunately, little can be learned from Graff's later work, which is an abject concession to the fallacies of academic political correctness.)

Politics by Other Means, by David Bromwich, is a many-sided defense of individualism in literary study. Bromwich offers cogent reasons for believing that even literary tradition is not simply a "social" artifact but is actively created by the choices of writers and readers. Papers by Stephen Cox criticize current academic tendencies on the basis of classical-liberal assumptions about the agency of the individual and the importance of rational procedures in analysis and theory.

The "Chicago School" of Criticism

The foundations of current theories had, in fact, been undermined long before the theories themselves appeared. The so-called Chicago Critics, who flourished in the 1950s, constructed defenses of authorial intention and critical objectivity that continue to repay close study. Chief among the Chicago Critics were R.S. Crane and Elder Olson, both powerful advocates of Aristotelian theory.

To a great degree, Crane and Olso defined themselves by opposition to the "New Criticism," a tendency that once dominated academic theory and that still exerts and influence on practical criticism. The New Critics justly opposed people's perennial inclination to reduce the meaning of literature to a paraphrasable "message." What was important to the New Critics was the richness of the literary text itself, not the circumstances in which was written or the moral or political causes in which it might be enlisted. But the New Critics often proceeded as if the text could be understood apart from any consideration of authorial intentions. They neglected the author's ability to impose structure by using objectively ascertainable textual markers to include certain meanings and exclude others. As a result, they sometimes discovered as many "meanings" in a text as their own ingenuity could possibly supply. "Meanings" that flatly contradicted either one another or any conceivable authorial intention were construed as "ironies" and "tensions" that "enriched" the overinterpreted text.

This defect of the New Criticism was exposed with devastating effect by Olson and Crane, who tried to revive interest in the author's power to unify and control the text. Crane developed some of the best evidence for this power in his studies of the great unifying device of plot. Crane and Olson also demonstrated the importance of understanding ways in which authors work with specific literary forms to accomplish their intentions. Olson's The Theory of Comedy, which illuminates a form that is notoriously resistant to analysis, is particularly worthy of notice.

The Chicago Critics' investigation of major literary forms and effects was pursued by Wayne Booth in two important books: The Rhetoric of Fiction, a learned analysis of the novel form, and A Rhetoric of Irony, a provocative attempt to explain the ways in which authors communicate certain meanings by pretending to communicate others. E.D. Hirsch, Jr., continued and advanced the Chicago Critics' work on authorial intentions. His Validity in Interpretation and The Aims of Interpretation are the most distinguished books on the subject. Hirsch attempts to vindicate a literary theory that gives full weight to authors' intended meanings. Do authors really know their own intentions? Doesn't the meaning of a text change over time? How can we be sure that the meaning we find in a text is the same one that the author intended? Hirsch's answers to these and other questions provide a persuasive defense of intentionalist theory as a basis of literary interpretation. Hirsch also provides sound arguments for regarding theory and interpretation as rational and objective processes.

Hirsch's discussion of the determinacy of authorial meanings is especially important to consider at a time when many prominent theorists assert that the meaning of a text necessarily varies with the race, class, and gender of its audience. Hirsch makes a useful distinction between meaning and significance: various readers may regard a text as significant to them in various ways, but they are responding, still, to the same text, a text with particular meanings, established by a particular author.

The Implications of Theory

The fashionable claim that the meaning of a text is "constructed" by the various contexts in which it is read should remind of us what is at stake in literary theory. Debates about theory are concerned with something more important than rival approaches to obscure poems. Ultimately, literary theory is about the human mind and its processes of communication. It is about our ability to understand what people say, write, and mean. Literary theory is a ferociously contested field because it has crucial implications for every other field that is based on the interpretation of words.

What we know about the world, especially the world of the past, comes largely form written documents. Our confidence in our ability to understand the world depends on our possession of sound working theories about the way in which texts communicate ideas across formidable barriers of time and cultural difference. Those "multiculturalists" who deny the validity of general and objective statements about the human condition are frequently inspired by literary theories that induce scepticism about people's ability to communicate their meanings across cultural and temporal barriers. Influential schools of legal thought that subject Constitutional rights to endless reinterpretation "in the light of current circumstances" depend on theories that posit the unknowability or irrelevance of the Founding Fathers' literary intentions.

To these intellectual and political problems, the solution is not less concern with literary theory but a better understanding of its principles and possibilities.

Bibliography

Many of the titles in this listing are available at Amazon.com. If you use this link, or the search box below, then IOS will earn a commission from Amazon.com on each book purchased.

Aristotle. Poetics.

Wayne C. Booth. The Rhetoric of Fiction. 2nd ed. Chicago. University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Wayne C. Booth. A Rhetoric of Irony. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

David Bromwich. Politics by Other Means: Higher Education and Group Thinking. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Biographia Literaria.

Stephen Cox. "Devices of Deconstruction." Critical Review, 3 (1989), 56-75.

Stephen Cox. "Literary Theory: Liberal and Otherwise." Humane Studies Review, 5 (Fall 1987), 1, 5-7, 12-14.

R.S. Crane. The Idea of the Humanities and Other Essays Critical and Historical. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967.

R.S. Crane, ed. Critics and Criticism: Ancient and Modern. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952.

Frederick Crews. Skeptical Engagements. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Gerald Graff. Literature Against Itself: Literary Ideas in Modern Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

E.D.Hirsch, Jr. The Aims of Interpretation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

E.D.Hirsch, Jr. Validity in Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967.

Samuel Johnson. Preface to Shakespeare.

Elder Olson. On Value Judgments in the Arts and Other Essays. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

Elder Olson. The Theory of Comedy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1968.

Alexander Pope. An Essay on Criticism.

Ayn Rand. The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature. Rev. ed. New York: New American Library, 1975. (Available from The Objectivism Store)

Percy Bysshe Shelley. A Defence of Poetry.

2 komente:

It's been a while since I've seen these interviews. thank you for reintroducing me to Ayn Rand.

well, i've had an on-off love affair with ayn rand ever since i read her novels and non-fiction way back in high school...regardless of my mixed feelings about her now, i can say with some confidence that i probably would never have become interested in philosophy if it were not for her. from ayn rand i went on to nietzsche and then to the postmodernists and the eastern mystics and the integral philosophers...the rest is history.

Posto një koment