U.S. Details Some Data-Mining Programs, Hints at Others

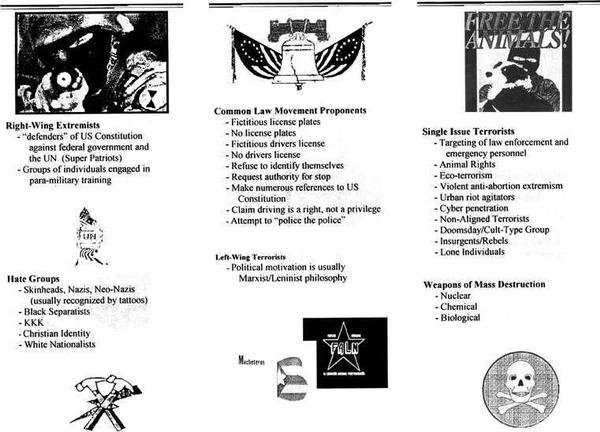

Justice Department and Homeland Security inspectors slid a broad range of government data-mining programs under a microscope last week in two reports to Congress that covered systems both sinister and banal.

But while the reports -- required under two separate federal laws -- convey a sense of the breadth of these powerful agencies' data mining, they only hint at several projects powerful enough to accidentally land innocent Americans in the cross hairs of the government's antiterrorism efforts.

On the innocent side, the Justice Department has separate data-mining programs to ferret out identity-theft gangs, Medicare fraud, staged automobile accidents, online pharmacy scams and illegal housing sales, according to the report (.pdf) by Justice Department Inspector General Glenn Fine. Some of that data mining is conducted with tools available to anyone with a copy of Microsoft Office. And once anomalies in the data are identified, agents follow up on the leads.

A more ambitious system under development will be used by the Foreign Terrorism Tracking Task Force -- an FBI group responsible for preventing terrorist attacks inside the United States. Called the System to Assess Risk, or STAR, the program will let agents enter names of suspected terrorists into a computer, which then calculates how likely each of those people is to pose a terrorist threat, based on 35 factors.

Data mining in the broad sense is everywhere these days, from online services that analyze blog server logs to supermarket loyalty cards used to decide what coupons are mailed to shoppers' houses. The term has many meanings, but usually refers to attempts to use smart algorithms to discover unseen patterns in large pools of data.

The most notorious government data-mining effort was Darpa's highly secretive Total Information Awareness program, which would have crawled through every possible database, public and private, to identify potential terrorists in the planning stages of an attack. In 2003, amid privacy concerns, Congress stepped in to defund much of that effort, and sent components of the program into the black budget with the promise that the tools would only target non-Americans.

The lesson learned by architects of other would-be future-crime-detection programs was to keep a low profile, avoid creepy names and don't create logos like Total Information Awareness' omniscient eye in a pyramid peering down on the globe.

The inspector general's report adopts a rosy view of Justice Department efforts. Most significantly, the report finds no cause for concern in the government's use of information provided by private data aggregators, despite the industry's history of producing inaccurate data that's been used to disenfranchise voters, deny housing and wrongly terminate employees.

The report's description of STAR is also sloppy. Throughout the analysis, the report says STAR relies on data aggregator ChoicePoint. But the graph explaining the data flow shows that the system queries Accurint, a massive database of public records ranging from fishing licenses to bankruptcy proceedings. That system is owned by LexisNexis, a ChoicePoint competitor.

Congress limited the Justice Department inspector general's report to programs that look for patterns in data -- a program that examines firearm registrations to figure out which gun owners are likely to commit homicide, for example. That definition excludes any programs where a system works by entering a person's name and then assigning them a terrorist threat rating, as the government does at the border and has proposed doing for domestic air travelers.

That's why the report mentions but does not elaborate on what looks to be the Justice Department's most aggressive use of information technology, the Investigative Data Warehouse. The search-engine-like tool lets investigators search 45 different databases simultaneously, including databases of phone and internet records collected through self-issued subpoenas.

The FBI is looking to expand that tool into a full-fledged data-mining system, but dodges press questions and ignores sunshine requests related to it.

Congress also stipulated that the inspector general's report shouldn't look at any system that doesn't use privately purchased data, or data collected by the government for non-investigative purposes.

Similar limitations cripple the usefulness of the Department of Homeland Security Privacy Office's report (.pdf), also provided to Congress last week.

There are hints that the Privacy Office shares concerns raised by an earlier audit over a new data-mining technology called Advise, which is being developed by DHS' science and technology group. The report passes along the news that development and testing of the program has been halted, pending further review.

But the report ignores one of DHS' most controversial uses of data, the Automated Targeting System, which uses secret algorithms to rate the threat level of every air traveler to and from the United States, regardless of whether they are citizens or not.

That system doesn't count for purposes of the report because it takes in names from passenger lists and spits out the people who allegedly deserve extra scrutiny at the border. Because it starts with a list of names, it isn't data mining, under the definition handed to the Privacy Office by Congress.

Try explaining that distinction to someone pulled aside for scrutiny at the border, who then has to plead for help from her congressional representative to get freed from the non-data-mining system's grasp.

Nuk ka komente:

Posto një koment